Each year the Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK organisation (MBRRACE-UK) provide a report on outcomes for women and another on outcomes for babies. The latest report for babies has just been published, summarising outcomes from 2023. I’m keeping an eye on the UK, as there as been a lot of work nationally to improve perinatal outcomes. This includes recommendations made in response to several investigations into poor outcomes in specific trusts such as the appointment of Fetal Monitoring Midwives in each trust, the Each Baby Counts program, the Saving Babies Lives bundle, and more recently the Avoiding Brain injury in Childbirth (ABC) project, among others. If these were collectively effective, then sometime soon, improvements in outcomes should start to be obvious. So let’s see what there is to see in this report.

Birth rates

There were 661,008 births at 24 or more weeks of gestation age (excluding termination of pregnancy) in 2023. This is a fall of 18.3% from 2013, and a fall of 2.3% compared to 2022. This reduction in birth rate should, in theory take some pressure off over burdened services, assuming staffing rates remained stable.

Mortality rates for 2023

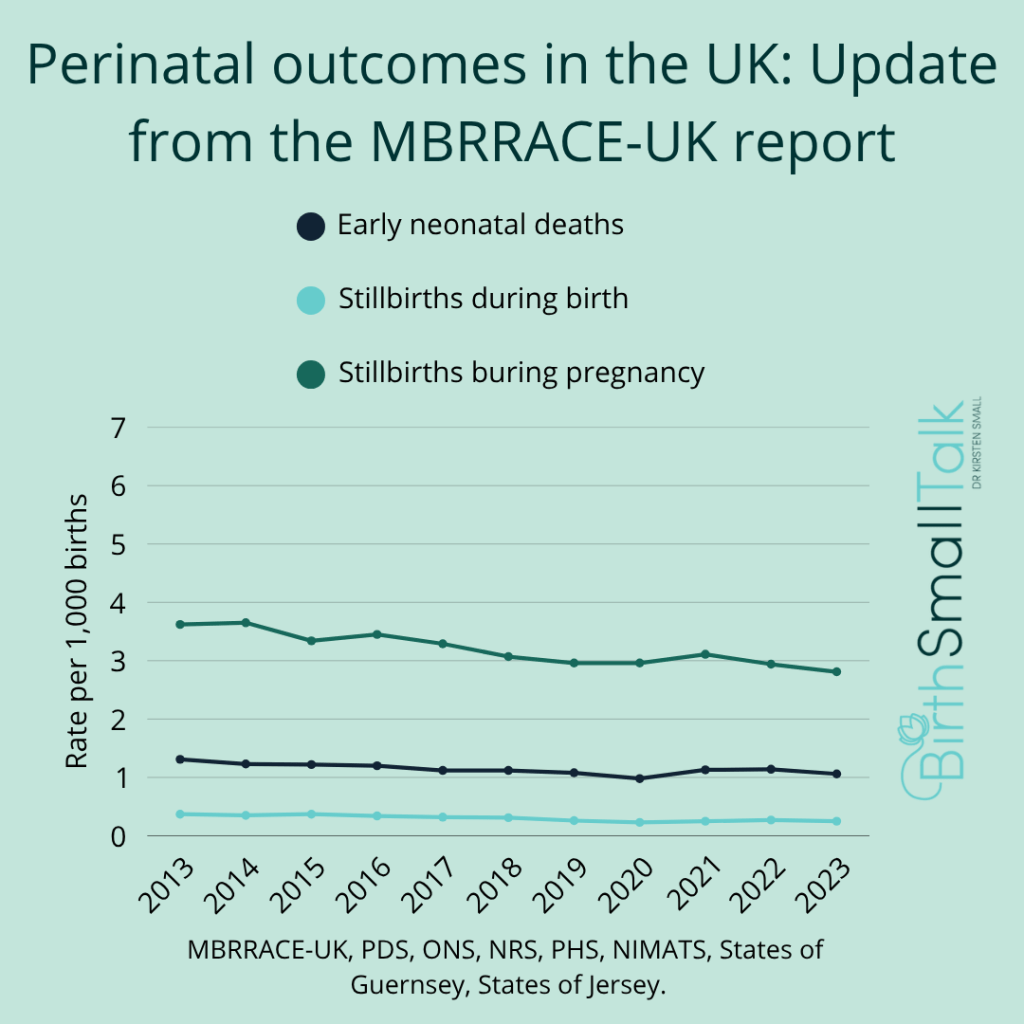

The report includes deaths of babies during pregnancy from 24 weeks on, excluding pregnancy termination, and death up to 28 days after birth. They report on deaths during labour and early neonatal death (the first seven days after birth) reported separately, which is useful as these are the deaths that fetal monitoring in labour is designed to prevent. They provide comparisons with the previous ten years. Looking at the different timings for mortality, the outcomes are:

- Stillbirths during pregnancy: There has been a fall from 3.62 per 1,000 births in 2013 to 2.81 in 2023. The stillbirth rate rose in 2021. This rise is likely secondary to both COVID and changes to service delivery during the pandemic. The 2023 rate is a slight improvement on the rate from 2019 (which was 2.96 per 1,000).

- Stillbirths during labour: The rate was 0.37 per 1,000 births in 2013. The lowest rate in the decade since was 0.23 per 1,000 in 2020. The rate rose again in 2021 and 2022, and in 2023 was 0.25 per 1,000.

- Early neonatal deaths: In 2013, the mortality rate was 1.31 per 1,000, falling to 0.98 per 1,000 in 2020. After rising again in 2021 and 2022, the 2023 rate was 1.06 per 1,000.

Similar patterns (though with slightly different rates) were seen across all four countries that make up the UK. Three quarters of the losses were in babies born before 37 weeks of gestation. Women from areas of socio-economic disadvantage and of non-White ethnicity continue to fare worse in all outcomes.

Do some Trusts do better, or worse, than others?

The report grouped Trusts according to the number of births annually and whether there was a level 3 neonatal intensive care unit on site or not, and then compared mortality rates in each trust within that group. Rates were also adjusted to take into account the women’s age at birth, their socio-economic deprivation level, their gestation at birth, and the babies sex, ethnicity, and whether they were part of a multiple pregnancy. Any remaining variation in mortality rates between trust should therefore largely reflect the quality of care provision, rather than case complexity.

For stillbirths, the rates cluster tightly, with little variation between trusts. However, for neonatal deaths, particularly in hospitals with a level three nursery, the range is wider. There are several places with much higher than average rates, and some of these persisted once the numbers were adjusted for congenital anomalies. The issue of the “postcode lottery” (you might be lucky to have a good performing service in your area, or you might not…) remains an issue for the UK. The report provides details for each Trust in the UK, so you can at least know what to expect at your local Trust.

Are things getting better?

It depends on what the goal was in the first place.

If we go back to the Each Baby Counts program, their goal was to achieve a 50% reduction in the combined rate of death and brain injury from the 2015 baseline of 1.57 per 1,000 term births. MBRRACE-UK don’t report on rates of brain injury, so we can’t look at progress for that outcome. MBRRACE-UK include preterm births so the rate is higher to begin with. If we apply the same measure of success, the rate of perinatal mortality (stillbirth + early neonatal death) was 5.09 per 1,000 births in 2015 in the MBRRACE-UK data. A 50% reduction would be a rate of 2.55 per 1,000. Instead, the rate was 4.28 in 2023. Clearly the target remains a long way off.

While this is moving in the right direction, the pace of change is very slow. The data from 2021 and 2002 impacted by the COVID pandemic illustrates how outcomes remain at risk from external pressures. While the UK are shovelling money and effort towards solving the problem, the return on investment appears to be low.

Why? If the interventions that are promoted as providing solutions to the problems are ineffective in the first place, then a lot of effort is simply wasted. I won’t comment on the place of induction of labour, ultrasound scanning for fetal wellbeing, and the pressure to shift women from midwifery-led to obstetric-led models of care, and so on, as they aren’t my area of expertise. However, I can state with confidence that investing in central fetal monitoring systems, computer interpretation, CTG education, and the development and enforcement of policies that see more women having CTG monitoring in labour will NOT produce the desired outcomes. If maternity services want to see significant improvements in outcomes, then it is time to admit that current fetal monitoring approaches don’t work and actively investigate other approaches that might solve this intractable problem.

Sign Up for the BirthSmallTalk Newsletter and Stay Informed!

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research and course offers? Our monthly newsletter is here to keep you in the loop.

By subscribing to the newsletter, you’ll gain exclusive access to:

- Exciting Announcements: Be the first to know about upcoming courses. Stay ahead of the curve and grab your spot before anyone else!

- Exclusive Offers and Discounts: As a valued subscriber, you’ll receive special discounts and offers on courses. Don’t miss the chance to save money while investing in your knowledge development.

Join the growing community of BirthSmallTalk folks by signing up for the newsletter today!

Sign up to the Newsletter

Reference

MMBRRACE-UK. (2025). UK Perinatal deals of babies born in 2023. State of the nation report. https://timms.le.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk-perinatal-mortality/surveillance/

Categories: CTG, EFM, Perinatal mortality, Stillbirth