My doctoral thesis is now out from embargo and freely available. Reading a doctoral thesis is hardly everyone’s idea of a great way to spend an evening (or several), but if you do decide to read it let me know what you think! You can access it here.

The abstract said:

The use of cardiotocograph (CTG) monitoring technology is ubiquitous in high-income countries. Central fetal monitoring technology has made it possible to observe a birthing woman’s CTG outside her birth room. Research regarding CTG monitoring demonstrates no significant benefits for the baby and increased rates of surgical birth for women. Very little evidence specifically addresses central fetal monitoring. Despite claims that obstetrics is evidence-based, obstetric organisations continue to recommend CTG monitoring.

My research took a critical feminist stance, questioning the relationships between obstetric power and central fetal monitoring. Using Institutional Ethnography, I examined how maternity clinicians’ intrapartum care provision was organised by, and in relation to, a central fetal monitoring system (K2) in an Australian maternity service. Four focus group interviews, 27 one-on-one interviews and 97 hours of observation were conducted. Relevant texts were also collected.

Midwives described a troubling social event, which they named being K2ed. Obstetric or senior midwifery staff would come into the birth room without the midwife requesting their presence. The staff member entering the room was almost always responding to a CTG interpreted as abnormal when viewed at the central monitoring screen. Midwives experienced being K2ed as intrusive and disruptive. I defined this event as the problematic for my inquiry.

Interviews and observations were transcribed, and along with texts, were indexed to identify and collate work processes, social relations and texts. Indexed data were analysed by questioning what they demonstrated about how being K2ed happened. The goal of analysis was to explicate the social and textual organisation of maternity clinicians’ work which made being K2ed possible.

The structure of the K2 system shaped the nature of data entered into K2 and midwives’ documentation work. Midwives worked with K2 to build a representation of the birthing woman, make decisions about initiating CTG monitoring, generate an interpretable CTG recording, interpret the CTG and take action in response to abnormalities. Obstetricians and the midwifery team leader read the data in K2 at the central monitoring screen. Contextual information available to the midwife working with the birthing woman was not visible at the central monitor.

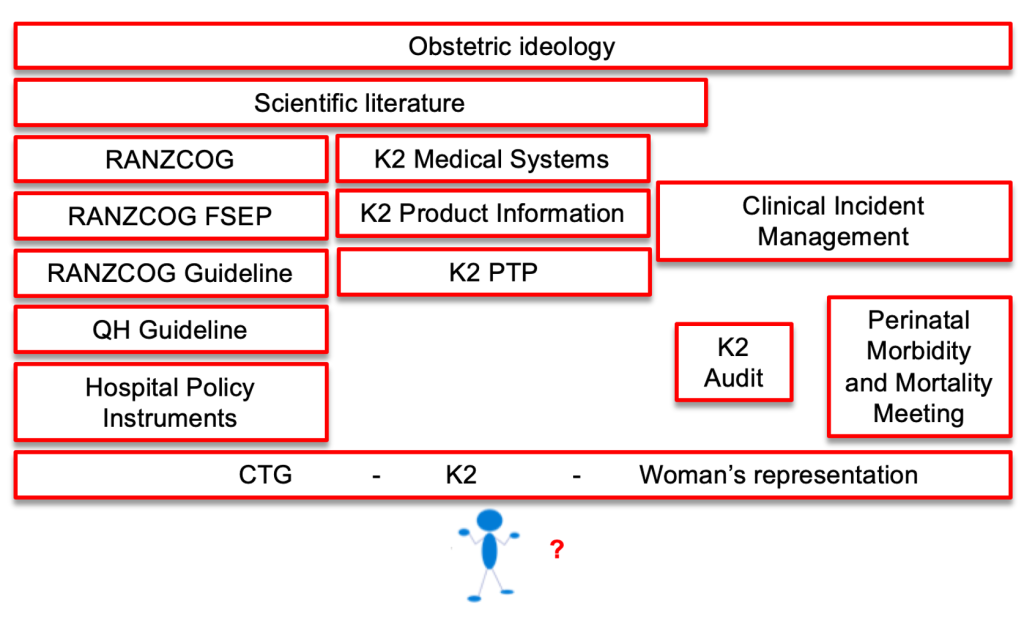

The decision to use CTG monitoring increased the probability of being K2ed. This decision was usually made by the midwife and was strongly structured by a set of texts. These texts also shaped expectations of midwives’ work in generating an interpretable CTG, defined how to interpret the CTG, and structured the actions taken when the CTG was categorised as abnormal. Tasks completed by obstetricians, such as fetal blood sampling, were not as strongly coordinated, leaving obstetricians with a degree of autonomy. Midwives were expected to escalate care to senior staff when the CTG was abnormal. This expectation supported being K2ed as a logical behaviour. If the clinician at the central monitor saw an abnormal CTG, and in the absence of contextual information to explain why escalation was not required, the clinician felt justified in going to the birth room when the midwife had not requested their presence.

The Intrapartum Fetal Surveillance guideline produced by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists established the discursive territory for other policy texts relating to intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring. Research regarding intrapartum CTG monitoring incorporated assumptions regarding birthing women (passive, risky), the fetus (precious, at risk) and midwives (lacking competence, needing supervision). These beliefs were translated from research into policy texts, the design of K2, and fetal monitoring education, and therefore entered the everyday work of midwives.

Using Institutional Ethnography to generate a map of social relations, I demonstrate that obstetric ideology acted as a ruling relation, structuring midwives work and reinforcing obstetric dominance in maternity care. Patriarchal views embedded within the textual organisation of the workplace shaped the way that birthing women were knowable and how maternity clinicians acted in relation to that knowledge. Honest conversations within obstetrics and more widely in maternity care are required to acknowledge the harms currently occurring from the use of central fetal monitoring systems. I conclude by suggesting that it is time that maternity clinicians challenged obstetric ideology and focused on growing midwifery as a better model for the future.

- Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of an abnormal fetal heart rate pattern in labour

- More evidence that intermittent auscultation is safe and effective

Categories: CTG, EFM, Feminism, IA, Obstetrics, Perinatal brain injury, Perinatal mortality

Tags: thesis

Hi Kirsten love the abstract. How do I access the complete work. I have always considered EFM as a way to keep women oppressed in labour, restrict their movement, make the focus of her experience about technology and ratchet up the fear about the babies well being as much as possible to ensure the woman’s compliance with institutional policies, that are not evidence based. So wrong on every level.

LikeLike

Send me your email address and I’ll see what I can do.

LikeLike

Hi Kirsten! I really enjoye reading the abstract. I would love receiving the entire complete work, if possible. My email address: HolisticHealthHelp@gmail.com Appreciation in advance of anything you could send my way. Blessings, ChristyLee, BCDNM

LikeLike