BirthSmallTalk is two and a half years old, with over 150 posts. The last few months have seen a bunch of new people join me. (Hello! And thank you for dropping by!) I’ve decided it is time to go back to some of the earlier posts to refresh and update them, and I’ve given the blog a fresh look. Over the next six weeks I’ll be revisiting posts covering some basic concepts and background information about what is going on with fetal heart rate monitoring.

Understanding how we arrived at this present point in the history of fetal heart rate monitoring helps to make sense of where we find ourselves. It is worth remembering the history of what we might call modern maternity care is quite short, and is still unfolding.

It’s hard to pick a moment in history to know where to start. Throughout history women have used many ways of knowing their own bodies and what is happening during pregnancy, labour, and birth. The gendered nature of what is considered important enough to commit to a lasting written record means there are few historical traces of this. The history of maternity care is essentially the story of men trying to make sense of women as a mysterious “other”.

There were mentions of listening to sounds within the body as early as the Hippocratic period (460 to 370 BC), but putting the listening ear directly on the body of the person was always a bit of a problem. This was solved by Rene Laennec, a Frenchman (1781 – 1826), who created a simple cone shaped piece of wood, rather like what we know now as a Pinard’s stethoscope. In 1819, Jacques Kergaradec (a student of Laennec) placed a stethoscope on the abdomen of a pregnant woman and wrote “It seemed to me that I was hearing the movements of a watch placed very close to me.” It occurred to Kergaradec that variations in the fetal heartbeat might form the basis of a judgement on the health of the fetus.

It is probably fair to say this is the moment fetal heart rate monitoring came into existence. This was the start of a significant shift in the focus of medical knowledge regarding pregnancy and birth. Prior to this point, doctors (men) had no tools to identify with accuracy whether a woman was pregnant, and if the fetus was alive and healthy, so there was little reason to invest time and energy focussing on something you couldn’t measure. (Of course, women had their own knowledge about all of this, but this was considered to be unreliable in matters of medicine or the law.)

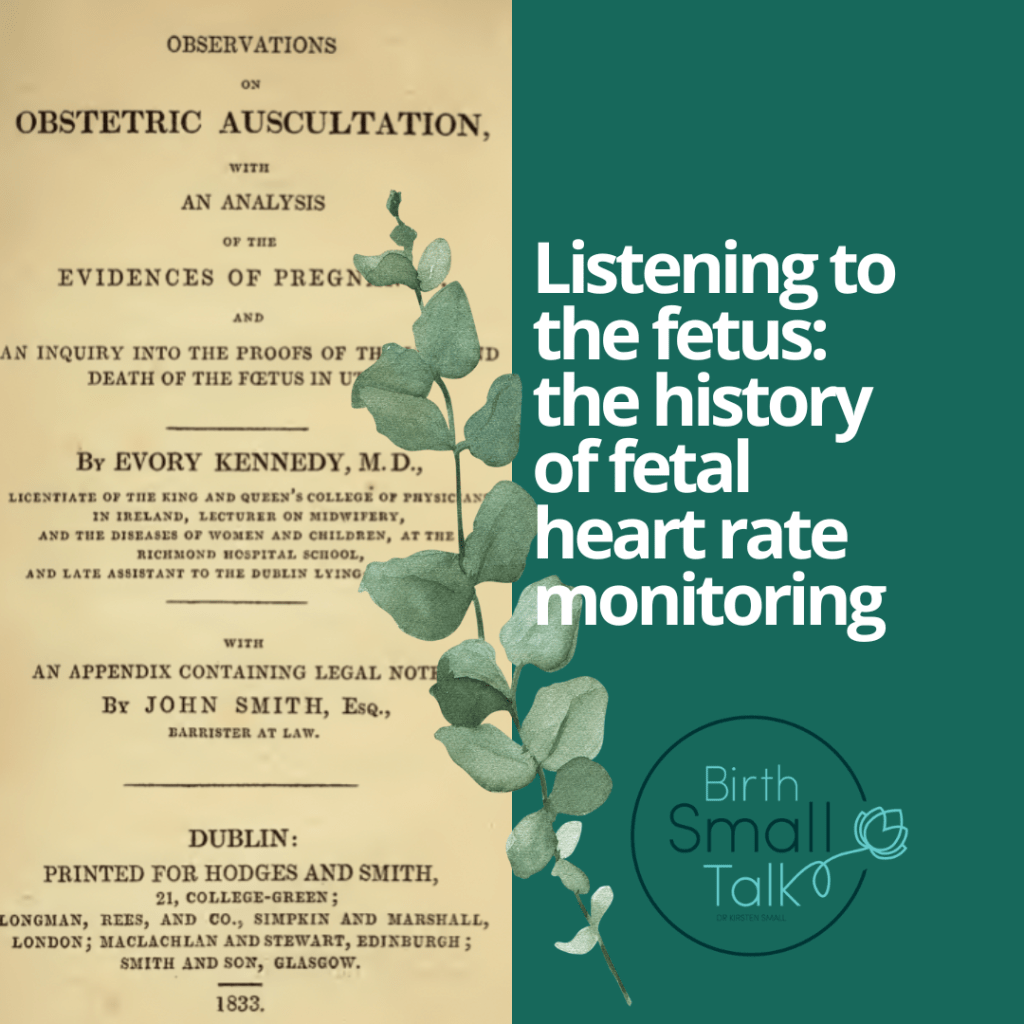

Within a few years, listening to the fetal heart was introduced to the National Maternity Hospital in Dublin, Ireland, and by 1833 was described as being in daily use. The main use was to diagnose fetal death, which permitted the use of instruments to remove the fetus in pieces and bring the labour to an end, in the hope of saving the life of the woman. This was during the period when death from birth related sepsis was commonplace and doctors were reluctant to acknowledge their own role in continuing the epidemic.

Running alongside the story of fetal heart rate monitoring, is the story of the development of safer surgical approaches to end labour – firstly forceps assisted birth, then the caesarean section. This eventually made it possible to achieve the birth of the fetus with an acceptable level of risk for the birthing woman (at least acceptable for the medical profession). Safer surgical birth shifted the focus of obstetric knowledge. No longer was the mother the primary patient, and the fetus a secondary concern. The well-being of the fetus became more and more important in obstetrics over time, so that by the mid 20th century, the fetus had become the primary focus.

Sign Up for the BirthSmallTalk Newsletter and Stay Informed!

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research and course offers? Our monthly newsletter is here to keep you in the loop.

By subscribing to the newsletter, you’ll gain exclusive access to:

- Exciting Announcements: Be the first to know about upcoming courses. Stay ahead of the curve and grab your spot before anyone else!

- Exclusive Offers and Discounts: As a valued subscriber, you’ll receive special discounts and offers on courses. Don’t miss the chance to save money while investing in your professional growth.

Join the growing community of birth folks by signing up for our newsletter today!

References

Arney, W. R. (1982). Power and the profession of obstetrics. University of Chicago Press.

Goodlin, R. C. (1979, Feb 01). History of fetal monitoring. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 133(3), 323-352. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(79)90688-4

Gültekin-Zootzmann, B. (1975). The history of monitoring the human fetus. Journal of Perinatal Medicine, 3(3), 135-144. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpme.1975.3.3.135

Gunn, A. J., & Wood, M. C. (1953). The amplification and recording of fœtal heart sounds [Abridged]. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 85-91. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/003591575304600206

Kennedy, E. (1833). Observations on obstetric auscultation: With an analysis of the evidences of pregnancy, and an inquiry into the proofs of the life and death of the foetus in utero. Hodges and Smith.

Pinkerton, J. H. (1969). Kergaradec, friend of Laennec and pioneer of foetal auscultation. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 62(5), 477-483. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4890358

Tanner, T. H. (1868). On the signs and diseases of pregnancy.

Tags: Dublin, Kergaradec, Laennec, Pinard