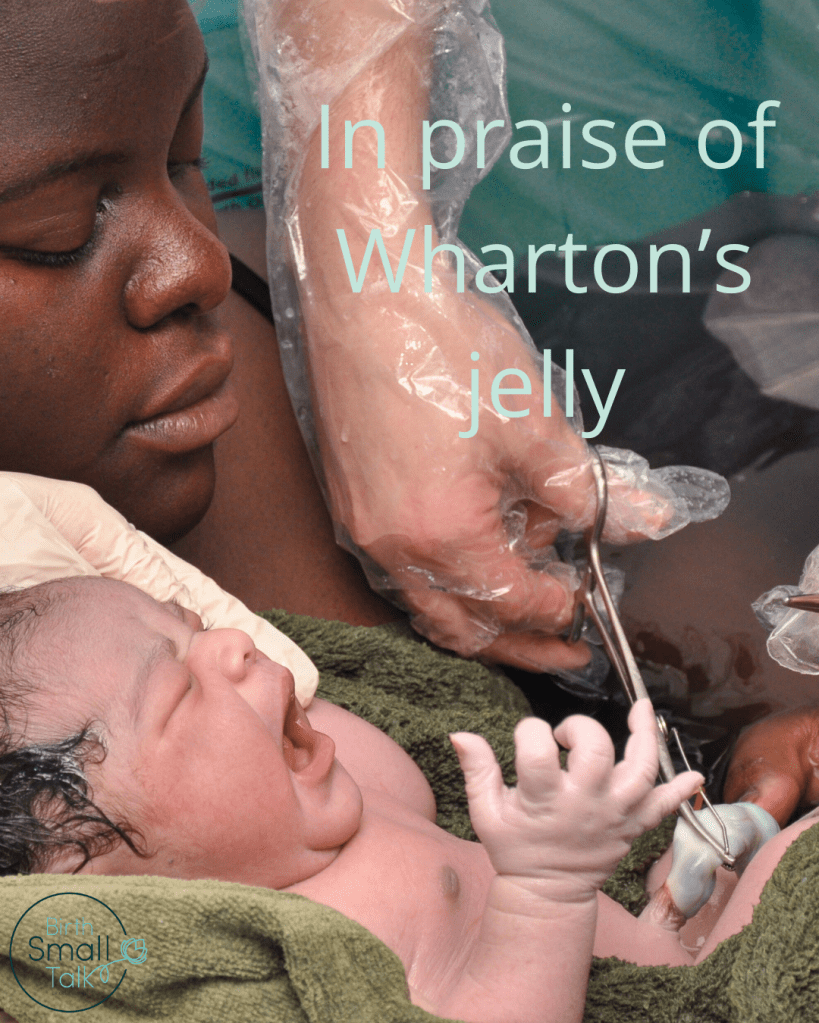

I find placentas and umbilical cords fascinating. They are all too often swept away soon after birth, discarded as detritus without much thought other than to consider whether or not a part of the placenta is missing. Women and their support people may not be offered a guided tour of this remarkable organ – and so many people in our culture have been led to think of the placenta and cord as rather revolting. I used to enjoy the post-birth ritual of looking carefully at both sides of the placenta, opening out the membranes to identify the opening the baby had made its escape through, and showing how a knot tied in the cord would simply slip off due to the “magical” properties of Wharton’s jelly – the transparent stuff that wraps about the blood vessels in the cord and provides it with structure.

My curiosity got the better of me when I spotted the title of this recently published paper: Ultrasound evaluation of the size of the umbilical cord vessels and Wharton’s jelly and correlation with intrapartum CTG findings (di Pasquo et al., 2025). I instantly clicked on the link to read what they had found. The authors set out to see if there was a link between the amount of Wharton’s jelly in the cord and fetal heart rate patterns during labour.

What did they do?

Women who presented to one hospital in active labour (defined as having a cervix that was at least 6 cm dilated with more than three contractions every ten minutes), who were at least 37 weeks pregnant with one head down baby, and who were using CTG monitoring were asked to take part in the trial, as long as the CTG was considered normal at the time. Those who agreed to take part had an ultrasound scan where measurements of the size of the umbilical cord and the blood vessels in it were taken. (The authors don’t say which part of the cord the measurements were taken of – the cord isn’t consistently the same thickness along its full length.) The professionals providing care were not told these results, so they would not impact on the way care was provided.

After birth, the CTG recordings from the first stage of labour were evaluated by two obstetricians (who also did not know the scan results). They looked for repetitive decelerations and calculated the total deceleration area (a measure of how much time the fetal heart rate was below baseline over time) for the first stage of labour, and for the time period after membrane rupture. This information was then combined with the ultrasound results, and statistical analysis was used to explore the relationships between them.

What did they find?

In total, 113 women contributed data to the study. Of these, 60% were giving birth for the first time, with an average gestational age of 39 weeks and 6 days. Repetitive decelerations were present in the CTG recordings during the first stage of labour for 19% of the women. Women with repetitive decelerations were more likely to have less Wharton’s jelly (a smaller sized cord). The total deceleration area for overall first stage and for the time after membrane rupture were also correlated with the amount of Wharton’s jelly.

What does this mean?

The authors discussed the presumed role of Wharton’s jelly acting to prevent compression of vessels in the umbilical cord and therefore maintaining adequate delivery of oxygen to the fetus. They incorrectly link cord compression with activation of baroreceptors as a cause of decelerations in the heart rate (something that recent physiology research has called into question). The other thing these authors get wrong is the statement that:

the frequency and depth of the fetal decelerations registered on intrapartum CTG consistently increase the risk of fetal compromise or injury.

Fetal decelerations are a mechanism for coping when oxygen levels fall. By reducing the heart rate, the heart’s need for oxygen is reduced and therefore damage from low oxygen levels is avoided (at least until the coping mechanism reaches its limit). Decelerations don’t cause fetal compromise or injury – they are one sign that a process of acting to prevent injury has been activated.

The authors suggest that perhaps women could be screened during pregnancy with an ultrasound measurement of the size of the umbilical cord, suggesting “continuous intrapartum monitoring, more judicious use of oxytocin, and if indicated, amnioinfusion” as a way to prevent decelerations. There is, of course, no evidence that increased intensity of fetal heart rate monitoring can improve outcomes. And oxytocin should only ever be used judiciously, irrespective of what an ultrasound might say about the size of the cord.

While the paper helps to provide a tiny bit of new information that is useful for understanding fetal physiology, they authors don’t appear to have a good working knowledge of current research about fetal heart rate physiology and simply restate the common myths. I continue to remain in awe of the beauty and functionality of umbilical cords and their translucent Wharton’s jelly!

Sign Up for the BirthSmallTalk Newsletter and Stay Informed!

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research and course offers? Our monthly newsletter is here to keep you in the loop.

By subscribing to the newsletter, you’ll gain exclusive access to:

- Exciting Announcements: Be the first to know about upcoming courses. Stay ahead of the curve and grab your spot before anyone else!

- Exclusive Offers and Discounts: As a valued subscriber, you’ll receive special discounts and offers on courses. Don’t miss the chance to save money while investing in your knowledge development.

Join the growing community of BirthSmallTalk folks by signing up for the newsletter today!

Sign up to the Newsletter

References

di Pasquo, E., Dall’Asta, A., Volpe, N., Corno, E., Di Ilio, C., Bettinelli, M.L., & Ghi, T. (2025). Ultrasound evaluation of the size of the umbilical cord vessels and Wharton’s jelly and correlation with intrapartum CTG findings. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology & Reproductive Biology, 305, 42-47. https://www.ejog.org/article/S0301-2115(24)00663-8/fulltext

Categories: CTG, EFM, New research

Tags: Baroreceptor reflex, Deceleration area, Decelerations, Physiology, ultrasound, Umbilical cord, Wharton's jelly

You might consider that the water component of Wharton’s jelly participates in the volume of water in the amniotic fluid (?oligohydramnios) and in the fetus itself (higher hematocrit) It is likely associated with alterations of ponderal index and other measures of fetal growth. Growth restricted fetuses were excluded from the study.

Τіtle of our аrtіcle: Approaches to Prеνеnting Intrapartum Fetal Injury

Authors: Schifrin, Koos, Cohen and Soliman. 2022

Abѕtrаct Electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) was introduced into obstetric practice in 1970 as a test to identify early deterioration of fetal acid-base balance in the expectation that prompt intervention (“rescue”) would reduce neonatal morbidity and mortality. Clinical trials using a variety of visual or computer-based classifications and algorithms for intervention have failed repeatedly to demonstrate improved immediate or long-term outcomes with this technique, which has, however, contributed to an increased rate of operative deliveries (deemed “unnecessary”). In this rеvіеw, we discuss the limitations of current classifications of FHR patterns and management guidelines based on them. We argue that these clinical and computer-based formulations pay too much attention to the detection of systemic fetal acidosis/hypoxia and too little attention not only to the pathophysiology of FHR patterns but to the provenance of fetal neurological injury and to the relationship of intrapartum injury to the condition of the newborn. Although they do not reliably predict fetal acidosis, FHR patterns, properly interpreted in the context of the clinical circumstances, do reliably identify fetal neurological integrity (behavior) and are a biomarker of fetal neurological injury (separate from asphyxia). They provide insight into the mechanisms and trajectory (evolution) of any hypoxic or ischemic threat to the fetus and have particular promise in signaling prеνеntive measures (1) to enhance the outcome, (2) to reduce the frequency of “abnormal” FHR patterns that require urgent intervention, and (3) to inform the decision to provide neuroprotection to the newborn.

I would welcome the opportunity to chat.

Barry S. Schifrin, MD

bpminc@gmail.com

LikeLike

Sure Barry – you’ll find my email address on my About page.

LikeLike