My doctoral thesis includes sections where I took a long hard look at the 3rd edition of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ (RANZCOG) Intrapartum Fetal Surveillance guideline (2014). I thought I had a good handle on it before I started the PhD, because I referred to it often when I worked clinically. Analysing it for my research meant asking a new set of questions as I looked at it, and I saw things I had not noticed previously.

RANZCOG released its fifth edition of the guideline in November 2025. I have already written about some of the positive changes this edition brings. Today, I want to make some direct comparisons between these two versions of the guideline to show you what has changed. (By the way – I’m planning a workshop on how to get the best from the guideline. Let me know what you would like me to cover.)

Women as decision-makers

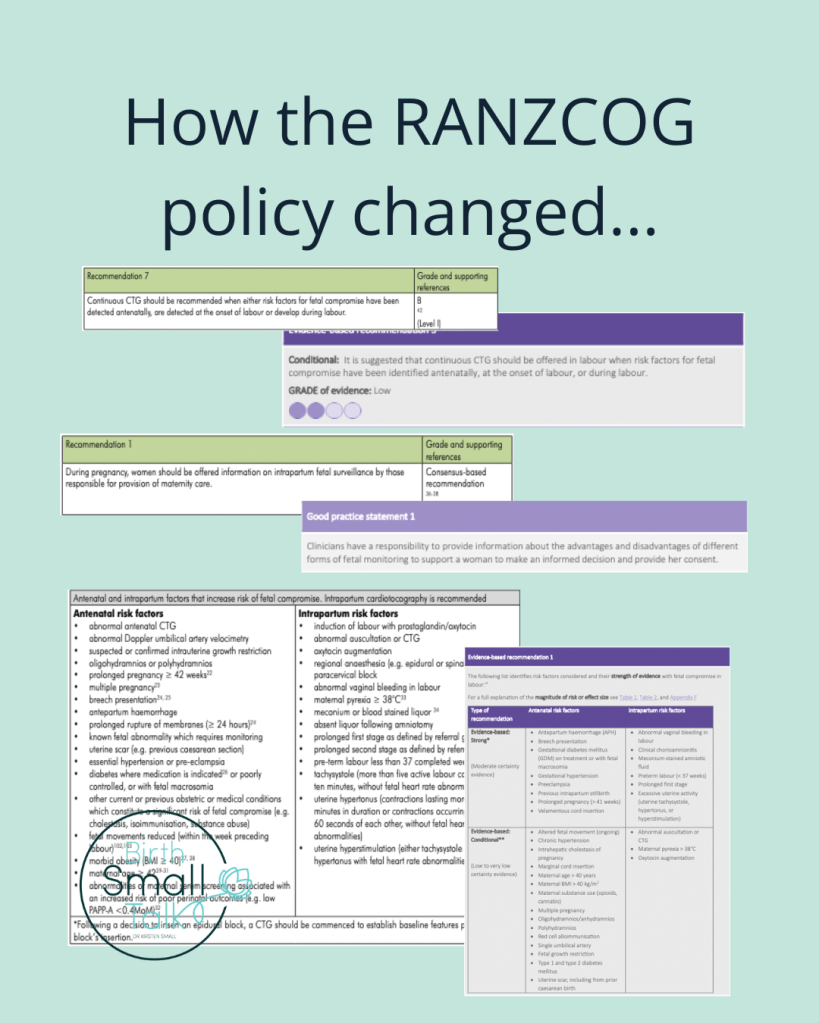

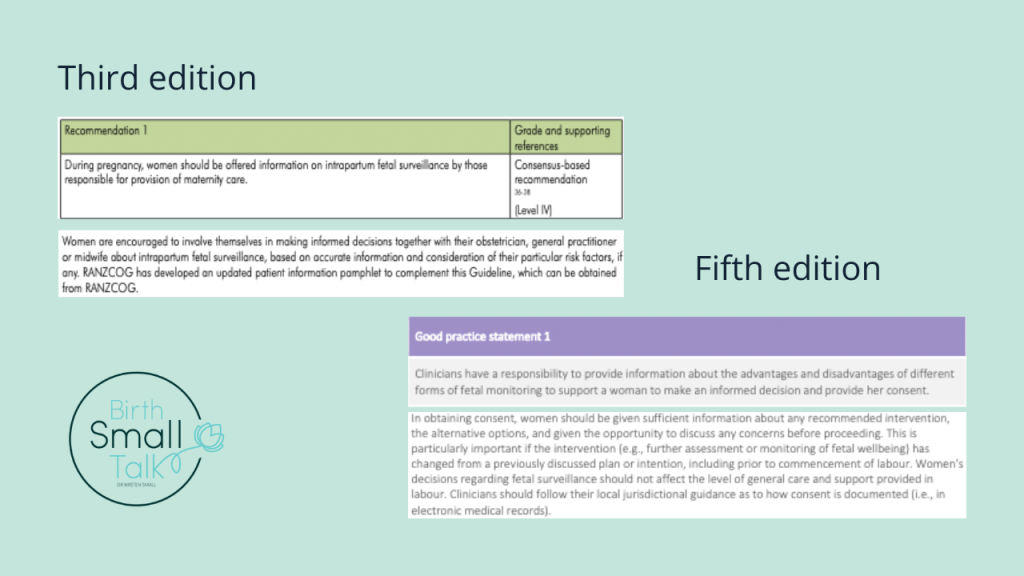

Back in 2020, I criticised the sentence in the preamble for recommendation one that said “Women are encouraged to involve themselves in making informed decisions together with their obstetrician, general practitioner, or midwife about intrapartum fetal surveillance, based on accurate information and consideration of their particular risk factors, if any.” (RANZCOG, 2014, p. 24). Here’s what I wrote in the thesis:

“This positioned decision-making as a choice that birthing women might opt into, rather than reiterating that only the birthing woman possessed authority to make decisions about her body. For a decision to be considered as “informed”, birthing women had to consider “accurate information” and “risk factors”. Obstetric views strongly shape risk conceptions in relation to fetal monitoring and are also likely to frame what is considered as “accurate information”. For the birthing woman’s decision to be seen to count by obstetric standards, she needed to make use of obstetric knowledge” (p. 228).

The recently updated edition makes a clear shift. Responsibility for engaging with information now resides with the clinician, rather than with the woman, and the role of the clinician is “to support”. Specific guidance about what to discuss is now set out. The requirement for consent prior to any form of fetal monitoring being used is now explicit rather than implied. This goes a long way towards restoring women’s decision-making authority that was stripped away in previous editions.

Evidence for CTG use for women considered to be a higher risk

Like other guidelines, RANZCOG uses the claim that their guideline is “evidence-based” as a means to establish their authority to tell professionals what they should do. In a section of my thesis titled “Not all that glitters is gold”, I provided several examples of how RANZCOG misrepresented evidence in the guideline.

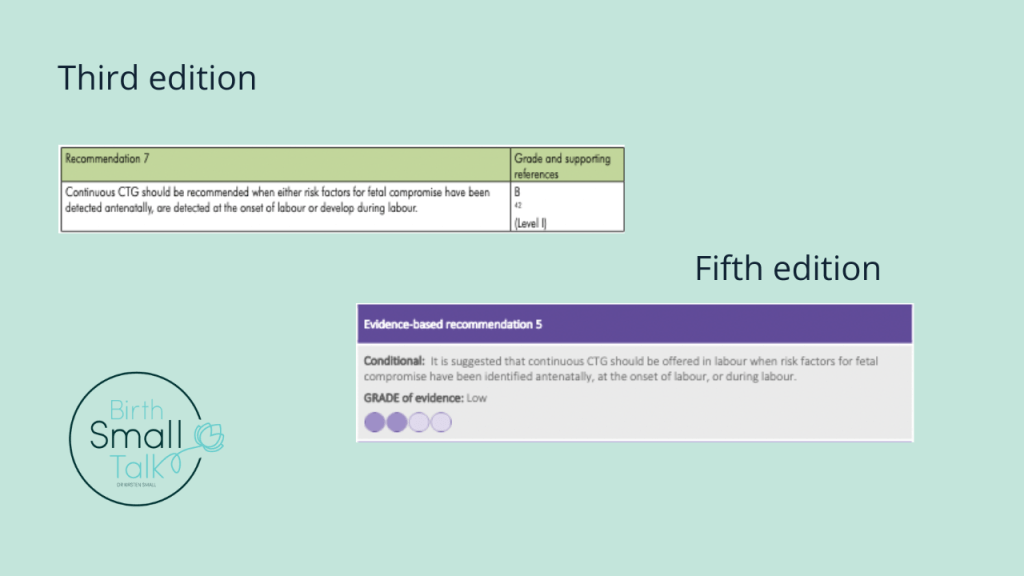

The most egregious of these was in what was recommendation seven, and is now recommendation five. The third edition referenced the 2013 Alfirevic et al Cochrane review, saying that this provided Level I (the highest form of) evidence for their recommendation for CTG use for women with one factors for fetal compromise. I wrote “the Cochrane review concluded that intrapartum CTG monitoring for women with risk factors was not associated with improved perinatal outcome, making it impossible to reconcile the recommendation with this evidence” (Small, 2020, p. 244).

The new edition now lists the evidence for this recommendation as “low grade”. Further down the document, there is an accurate summary of the evidence in the 2017 version of the same Cochrane review:

“among the subgroup of high-risk pregnancies continuous CTG may be associated with a higher rate of caesarean birth and may have little or no impact on perinatal mortality or neonatal seizures. …. the use of continuous CTG was associated with an increased risk of cerebral palsy …”(p. 43).

The language structure of the recommendation has also been softened. There is now a “suggestion” that CTG monitoring be “offered”, rather than being a recommendation.

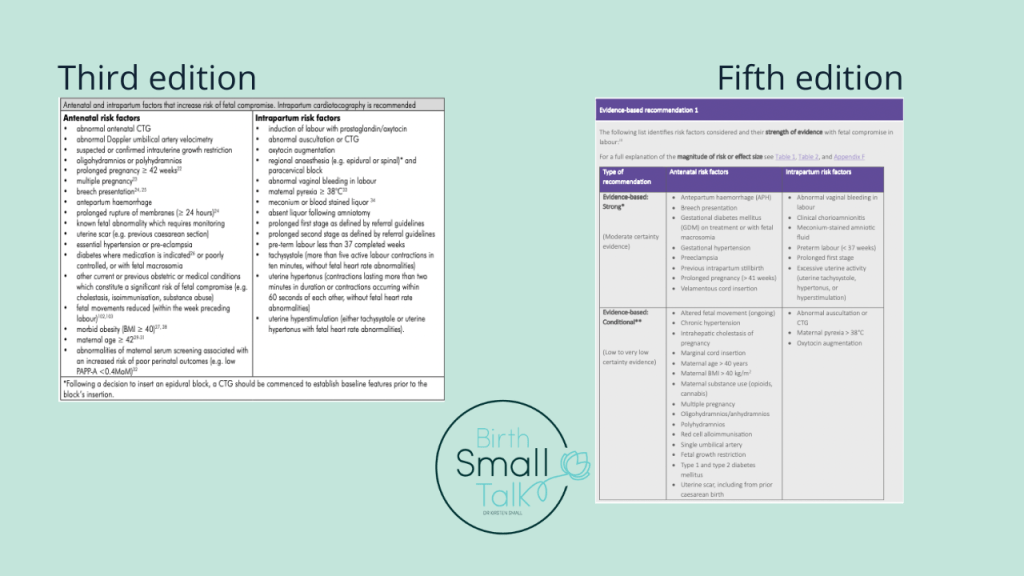

Evidence for the factors that identify women at higher risk

Both editions of the guideline feature a list of “risk factors that increase risk of fetal compromise”. The third edition explained the origins of this list for that edition (RANZCOG, 2014, p. 23):

The Working Party identified a number of risk factors listed below. Some where taken from previous editions of this Guideline, some were risk factors list in other international intrapartum fetal surveillance guidelines, and others were derived by consensus of the working party.

I wrote critically of the absence of evidence behind this list, saying:

Of the 32 risks listed, eleven were accompanied by a reference citation. Therefore, research evidence was used to support the inclusion of only one-third of the risks on the list. I selected two of the risk factors accompanied by a citation to explore further [maternal age and obesity]. … The evidence referred to did not support the contention that these factors generated a high risk for outcomes potentially modified by intrapartum CTG monitoring” (p. 247, 249).

The updated guideline does a much better job of making the certainty of the evidence (or lack of it) clearly visible. (Though as I showed last week, there remains room for improvement.) The list is now split into three, with risk factors compiled into sections where the evidence is “strong”, “conditional”, and those based on “clinical experience” only because the evidence is conflicting or shows no association with a worse outcome. Maternal age and higher BMI both appear in the “conditional” section, along with the explanation that there is “low to very low certainty evidence” to support their inclusion on the list.

Does this mean…?

At a quick glance it looks like someone at RANZCOG read my thesis and took the key messages to heart. It may or not have happened that way – I have no idea. But I do know that providing critical feedback on guidelines is a more effective pathway for change, than saying nothing.

These three particular changes have opened up an opportunity for maternity professionals to fundamentally change their approach to talking to women about fetal monitoring. These conversations can now be woman-centred, evidence-based, AND still follow the guideline to the letter.

Let me show you how…

I’ve created a workshop to help you get the best out of the RANZCOG fetal monitoring guideline. Among other things, I will take you through what has changed and what hasn’t; your new obligations under the guideline, how to make the most of the opportunities they open up, and potential traps to be aware of; and why there’s more work to be done and what you need to do next…

Access the workshop materials for 12 months for only $79 AUD.

References

Alfirevic, Z., Devane, D., & Gyte, G. M. L. (2013, May 31). Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5, CD006066. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006066.pub2

Alfirevic, Z., Devane, D., Gyte, G. M. L., & Cuthbert, A. (2017, Feb 03). Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2(CD006066), 1-137. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006066.pub3

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. (2014). Intrapartum fetal surveillance. Clinical guideline (3rd ed.).

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. (2025). Intrapartum fetal surveillance. Clinical guideline (5th ed.). https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/Intrapartum-Fetal-Surveillance.pdf

Small, K. A. (2020). Social Organisation of the Work of Maternity Clinicians Related to a Central Fetal Monitoring System. Griffith University. http://hdl.handle.net/10072/392850

- I’m 41 weeks pregnant. What’s the deal with CTG monitoring?

- There’s an invisible human rights issue in maternity care – let’s talk about it

Categories: CTG, EFM, Reflections, Language, Obstetrics

Tags: Consent, decision making, Evidence-based, guidelines, RANZCOG